The first time I inspected compiled code, I thought I was reading hieroglyphs.

And it was just compiled C++ that displayed “Hello World”…

The further we remove ourselves from the compiler, the more foreign it seems.

But these tools are so incredibly crucial to modern software development.

And we might go our entire careers without even giving them a true deep dive.

But that might be the point…

The compilers have been battle tested over time, so we trust their output.

If every person building software had to inspect their compiled code, nothing would ever get done.

And this is a good thing. This is progress.

So, what is a compiler anyway?

Let’s see what IBM has to say.

“A compiler is a type of computer program that converts code from one programming language (the source language) into another programming language (the target language).”

Okay, simple enough.

But when I think of compilers, I typically view them on a complexity axis.

Translating from a less complex language, to a more complex language.

Complexity could be lexical, but complexity could also be operational.

Ahh, they continue.

Compilers are used to transform high-level source code into low-level target code (such as assembly language, object code or machine code) while preserving the program functionality.

There’s the kicker, “preserving the program functionality”.

So another way to say this could be, “translating the intent from one language to another”.

Compilers are intent translators, that have some specialized knowledge about the best way generate code for the lower-level language.

Typically, this knowledge is gained over a long period of time, and it grows to a point of near full trust from its users.

Hmm, sounds familiar, right?

If you open up Cursor (like I do every day), and see the beautifully simple box below, you are viewing an intent capture element.

Cursor agent prompt box

This is the way that we currently assign intent, via a text box.

You type (or say!) something like “Create a web application that monitors the temperature in my house, and alerts me when it is out of the bounds I set. Hook up to the Nest API to get the data”.

Your intent is to do exactly that.

And because English (or whatever your native language is) is more descriptive than a constrained programming language, the time it takes to describe your intent dramatically decreases.

This system (which is backed by one or many generative AI models/agents) will translate your intent into whichever programming language, program, and pattern it sees fit.

Of course, there will be multiple passes at this as you try out the first few versions it generates, but over time, it should converge on a working solution.

It could be said that this system is compiling English into an application.

Therefore, the AI is an English compiler.

Like mentioned above, it will take more time until these tools approach near full trust from users, but all compilers have to start somewhere.

I’d be surprised if we don’t continue build trust over the next few years, especially for specific types of intent.

For example, maybe we learn these systems are incredibly accurate for web application intent, but need work on mobile application intent.

Maybe we see more mistakes in certain domains, like low connectivity applications, or on-premise application.

Only time will tell.

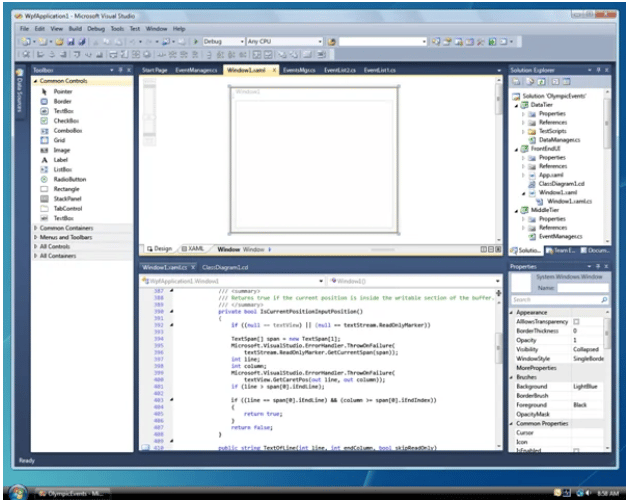

If any of you remember, an IDE like the below (Visual Studio) was how we would capture intent if we were building this temperature checking application in 2010.

Link

Looks a bit more complex, right?

The time it would take to get from zero to the intent described above for our application was orders of magnitude higher.

At this stage, the developer was the English compiler, translating your idea into a high level language like Java, and then using a C++ compiler to translate to a runnable application.

So, in the end, we are ceding some of our English compiler tasks to these generative AI systems.

Which means we can spend our energy on other parts of building.

I’m all for it.